“ Nation is a daily plebiscite“

Ernest Renan

Abstract. The results of the Romanian Census (November 2011) have been recently published. Scholars and politicians in Europe might be interested in the results, because comparison with the previous Censuses enables to trace the processes of ethno genesis and acculturation of large cross-border minority – Ukrainian community in Romania. The national minority has survived in spite of the powerful assimilation pressure of the host state and the lack of a state support from the kin state.

The authors have analyzed the census of population in Romania starting from the year 1930 and taking the latest census of 2011, in the context of change in demographic size of the Ukrainian population. The census data were connected with changes in ethno-national policy of the Romanian government.

How does the real situation regarding the rights of Ukrainians in political, educational and religious spheres in Romania look like? The authors made an attempt to give satisfactory answers to these and other questions.

Keywords: Romania, Ukrainian Minority, minority rights, border region, assimilation, integration

In 1991 Anthony Smith published ”National Identity”, one of his famous books. The author explained the theory of “civic” and “ethnic” types of nations and nationalism. Nationalist movements try to unite and integrate often disparate ethnic population within the border regions into a new political community in the civic-territorial model of the nation. The movements try to expand the territory of the state by including their ethnic kinsmen abroad according to the ethno-genealogical model.

It is of great interest to investigate possible interplays of nations with different types of national formation within the border regions where they closely contact. A civic-territorial model of nation often cold-shoulders its ethnic kin minorities living abroad. The states with such type of formation of national projects often face aggressive ethnic pan-nationalism of their neighbours. It does not give them the possibility to fully integrate the representatives of national minorities living on their territory.

Though it is rather difficult to draw a boundary between the ethno-genealogical models of nationalism in the modern world, especially in Europe, one can trace certain tendencies indicating this or that model in Ukraine-Romania-Moldova triangle. As the rest, Ukraine and Moldova have to formulate a weak ethno national policy having more feature characteristics of a civic-territorial model on the reason of political and ethnic non-consolidation. Romanian politic elite has not got rid of the complex of “Great Romania” (Romania Mare) on the other hand. It is trying to support pan-nationalist movements of their kin-minorities in neighbouring states, particularly in the above-mentioned ones.

If we combine two models of nationhood with four strategies of acculturation according to J.Berry (1997) we can get some models of formation of inter-ethnic relations in border regions – (Table 1). The models have been explored in the Ukrainian – Romanian border regions.

Table 1. Models of acculturation in border regions

| Type of nation in

a kin-state |

Type of nation

in a residence state (host country) |

|

| Civic | Ethnic | |

| Civic | non –conflict integration | assimilation |

| Ethnic | segregation with elements of irredentism | segregation with conflicts |

- 1. Legislation of Romania in the Sphere of National Minorities

A political regime has cardinally changed three times in Romania for the last eighty years, since the first, based on modern methods Census in this country in 1930. Romania has evolved from the monarchy to a communist dictatorship that ruled nearly half a century, and after a Revolution in 1989, the state accelerated the democratic development of which led her to membership in NATO and the EU.

In post- communist Romania the rights of ethnic minorities who live on its territory are legally regulated. Namely, in the Fundamental law of the country – the Constitution of Romania( 2003) it is mentioned that “Romania is the common and indivisible homeland of all its citizens, without any discrimination on account of race, nationality, ethnic origin, language, religion, sex, opinion, political adherence, property or social origin”. It is also written in the Constitution of Romania that “the State recognizes and guarantees the right of persons belonging to national minorities to the preservation, development and expression of their ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious identity. The protection measures taken by the Romanian State for the preservation, development and expression of identity of the persons belonging to national minorities shall conform to the principles of equality and non-discrimination in relation to the other Romanian citizens” [1].

It should be also mentioned that Romania pays considerable attention to its Diaspora. In the Constitution of the state it is mentioned that the state supports strengthening of connections with the Romanians who live abroad and work for protection, development and expression of ethnic, cultural, language and religious uniqueness and adhere to the laws of the country whose citizens they are.

Romania ratifies a Frame convention of national minorities’ rights by the Law of Romania (April 29, 1995 №33). The Convention is the first multilateral legal document which has a force of law and is called to defend the rights of ethnic minorities, strengthens the respective principles in many spheres of social life. It ensures the absence of discrimination, promotes equality, encourages protection of culture, religion, language and traditions, freedom of meetings, speech, conscience and religion, access to mass media, relation and border cooperation, ethnic communities’ participation in economic, cultural and social spheres[2].

The Advisory Committee of the Council of Europe on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (2012) has noted that Romania has continued its efforts to protect national minorities. A number of positive steps have been taken in this area. The adoption of the Law on Education in 2011 provides Romania with a more detailed legal framework for education and establishes legal guarantees for persons belonging to national minorities. Romanian Parliament has still not adopted the draft Law on the Status of National Minorities which has been under consideration in various forms. The Advisory Committee noted that “consequently, persons belonging to national minorities find it difficult to set up organizations of national minorities and to benefit from particular provisions in the electoral legislation which establish favourable conditions for organizations of national minorities currently represented in the Council of National Minorities”[3].

In 2007 Romania ratified European Charter of regional and minority languages. According to the Law on the ratification of the Charter, its regulations are applicable to the following languages on the territory of Romania: Bulgarian, German, Russian, Serbian, Slovakian, Turkish, Hungarian, Ukrainian, Croatian, Czech, Albanian, Armenian, Greek, Yiddish, Italian, Macedonian, Polish, Rom, Ruthen and Tatar[4].

In 2011 Romania adopted a new Law on the national education which presupposes the right for national minorities to get education in their native language. Article 45 of the Law claims, “People who belong to national minorities have a right to study and have education in their native language at all levels, types and forms of education. Depending on local needs there may be formed, at the request of parents and group guardians, forms or schools with pupils who study in the language of a minority…”[5]. Besides, the Law presupposes that national minorities have a right for their representation proportional to the number of forms in school administration and county school inspections.

Bilateral agreements are an important element of normative regulation of ethnic minorities’ rights. The Agreement between Ukraine and Romania of good-neighbourly relations and cooperation was signed in 1997 in Chernivtsi. Article 13, comprising one-third of the Agreement, is dedicated to the rights of ethnic minorities. According to the article, the Sides decide to apply international norms and standards defining the rights of people who belong to national minorities, namely those norms and standards which are mentioned in the Frame Convention of European Council about protection of national minorities and also in other documents. At the same time it should be understood that these recommendations do not apply to collective rights and do not oblige the Agreement Sides to give the respective persons the right for special status of a territorial autonomy, founded on the ethnic criteria.

Ukraine and Romania promised to create equal conditions for people who belong to Ukrainian minority in Romania and Romanian minority in Ukraine to study their native language. At the same time both countries acknowledged the duty of the representatives of national minorities to be loyal to the host state and to its legislation.

- 2. Analysis of the population census data

Ukrainians are one of the most numerous (the fourth) national minorities in Romania. At the same time it should be mentioned that Romania has officially acknowledged ethnic groups of Ukrainians, namely “rusyns” and “hutzuls” as separate national minorities. Notwithstanding their scanty size (less that 1 thousand persons according to the census of 2012) “Rusyns” even received a representation in the Minorities Council in the Romanian Parliament.

The absolute majority of Ukrainians in Romania (about 80 per cent of the total population size) live in the regions bordering on Ukraine – Southern Bukovyna and Maramuresh area. This circumstance does not enable to consider Ukrainians in Romania being a diaspora community, instead of their long, several centuries compact residence on the territories neighbouring with Ukraine. It makes possible treating them as an autochthonous ethnic community which appeared to be beyond the territory of Ukraine only because of territorial demarcation of the XXth century.

According to the 2011 population census in Romania, 51703 people who declared their nationality as Ukrainians, live in this country. About 1000 people who identified their nationality as “rusyns” or “hutzuls” were specified in the column “other nationalities”. Nowadays, Ukrainians compactly inhabit four historical regions of Romania: 32631 people live in Maramuresh area (present counties of Maramuresh and Satu-Mare, 9848 people inhabit Banat (present counties of Timis, Arad and Karash-Severin), 6382 people – in Southern Bukovyna (present of Suceava County and part of the county of Botoshany), 1317 people – in Dobrudzh (the present County of Tulcea).

Comparison of the data of the 2011 population census of Romania with similar demographic data of censuses in the years of 1930, 1956, 1966, 1977, 1992 and 2002 enables us to analyse the tendency of change in the number of Ukrainians in Southern Bukovyna. It can be done in the context of similar changes of the number of ethnic Romanians and all the population. It also makes possible to compare the course of demographic processes in Romania and counties: Suceava and Maramuresh.

Table 2. Population of Romania

| Years of census | Population

|

||

| Romanians | Ukrainians | Total | |

| 1930 | 11,118,170 | 45,875 | 14,280,729 |

| 1956 | 14,996,114 | 60,479 | 17,489,450 |

| 1966 | 16,746,510 | 54,705 | 19,103,163 |

| 1977 | 18,999,565 | 55,510 | 21,559,910 |

| 1992 | 20,408,542 | 65,472 | 22,810,035 |

| 2002 | 19,399,597 | 61,098 | 21,680,974 |

| 2011 | 16,869,816 | 51,703 | 19,042,936 |

Note: data from: http://www.insse.ro/cms/files/RPL2002INS/vol4/tabele/t1.pdf

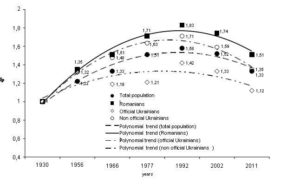

The authors suggested applying the Ip index of the Romanian population number for graphic comparison of demographic indicators of various ethnic communities incomparable by the scale which is calculated as a correlation of the data of six censuses with the respective data of the census from 1930. The population census in 1930 was taken as the basic one as it was the first to cover all the territories of modern Romania and contained the majority of demographic indicators applied in modern population censuses.

In general, demographic growth of all the population and the titular nation – Romanians and some other ethnic groups, in particular Ukrainians, was observed in Romania from 1930 to 1992. Thus, from 1930 to 1992 the population of the country (calculated within the boundaries of modern Romania) grew from 14,3 million to 22,8 million people (1,58 times more), Romanian population increased from 11,1 million to 16,2 million people (1,8 times more). However, the number of Ukrainians increased only from 45 thousand to 65 thousand people (1,42 times more). After 1992 the dominant demographic tendency in Romania was the decrease of the population size of the country. In 2011 population of Romania returned to the same indicators as they were in 1966.

The demographic situation in Romania during the last 80 years is described by polynomial trends in (Figure 1) in the first approximation.

Figure1. Dynamics of change in the index of the population (Ip) of Romania includes non official data (1930-2011)

General tendencies have been described above. A more detailed analysis of changes in the number of Ukrainian community of Romania reveals deviation from the polynomial trends of total population. The1966 and 1977 population censuses register sudden decrease of the number of Ukrainians by 12 per cent while the number of Romanians grows by 27 per cent. However, the 1992 population census indicated 20 per cent growth of Ukrainian population in Romania, which three times exceeded the similar indicator of population growth in the country.

It is impossible to find usual demographic explanations to such dramatic fluctuations which were happening during the life of one generation of Ukrainians in Romania, since at that time Ukrainian population of Romania suffered neither deportation nor repatriation (like in Poland), it did not starve either as people did in USSR. The reasons should be looked for in anti-Ukrainian policy of Ceausescu regime, during whose governing there were done the population censuses in 1966 and 1977 (Rendyuk, 2010:93). The destruction of Ukrainian-language education and Ukrainian public and religious life in Romania deprived Ukrainian community of any perspective of national development. As a result, thousands of Ukrainians who lived in the counties of Suceava, Botoshany and Tulcha stopped declaring their Ukrainian identity during the censuses in 1966 and 1977, moving to the category of “non-official” Ukrainians of Romania. The ruin of the communist regime in 1989 and Romania transition to a democratic development enabled more than 10 thousand of “non-official” Ukrainians to declare their Ukrainian identity in the1992 population census.

However, a considerable part of “non-official” Ukrainians of Romania have not returned to their own identity for this or that reason. A probable number of such “non-official” Ukrainians is illustrated in the respective polynomial trend made with consideration of the general demographic situation in Romania in the period between 1930 and 2011 and the coefficient of natural assimilation of Ukrainian population of Romania. There was used an assumption that assimilation of Ukrainian population in Romania was going on in favour of Romanian community. Taking it into consideration, we can see that demographic tendencies of Ukrainian community development in Romania suffered a considerable deformation under the influence of governmental assimilation policy of Ceausescu regime in 1960s-1980s. It caused an irreversible demographic shift – index of the number of Ukrainians if Romania made 1,12, while the average indicator of the population index of Romania made 1,33, and Romanians – 1, 51.

The process of national development of the Ukrainian community of Southern Bukovyna and Maramuresh area took place according to different scenarios, notwithstanding almost centennial residence of Bukovynians and Maramuresh Ukrainians in the neighbouring counties within the boundaries of one state and one legislative regulation of national minorities’ rights. The most vivid confirmation of the said is that though during the last 80 years there were no forced migrations or ethnic purges, the number of Ukrainians of Southern Bukovyna decreased several times and grew inconsiderably in Maramuresh area.

In the two neighbouring regions of the country, both of which border on Ukraine – Maramuresh area and Southern Bukovyna, at the beginning of the XXth century there lived approximately the same number of Ukrainians. Most of them lived in compact settlements (Ukrainians constituted 80-90per cent), the national centres of which were the towns of Seret in Southern Bukovyna and Siget in Maramuresh area with numerous and extended Ukrainian communities. However, the situation cardinally changed during the previous century.

At the beginning of the XXI century according to the official data of Romanian censuses the number of Ukrainians in Maramuresh County is four times bigger than the number of Ukrainians in Suceava County.

Table 3. Population of Maramuresh County

| Years of census | Population

|

||

| Romanians | Ukrainians | Total | |

| 1930 | 220,095 | 19,249 | 317,304 |

| 1956 | 285,341 | 25,435 | 367,114 |

| 1966 | 339,984 | 29,050 | 427,645 |

| 1977 | 394,350 | 32,723 | 492,860 |

| 1992 | 437,997 | 36,653 | 540,099 |

| 2002 | 418,405 | 34,027 | 510,110 |

| 2011 | 380,018 | 31,234 | 461,290 |

Note: data from http://www.insse.ro/cms/files/RPL2002INS/vol4/tabele/t1.pdf

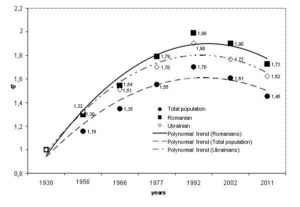

The demographic situation in Maramuresh County during the last 80 years is described in (Table 3) and polynomial trends are submitted in (Figure 2). The Diagram shows that Ukrainians of Maramuresh County managed not merely to preserve their identity in Romania under various governments which often carried the policy quite unfavourable for national minorities. Moreover, the number of Ukrainians in Maramuresh area increased symmetrically to the increase of the number of Romanians, even outgoing the dynamics of population growth of the whole county. Decrease in the number of Ukrainians of the county registered by the 2002 and 2011 population censuses can be perfectly explained by the tendencies of general demographic crisis in Romania in 2000s.

Figure 2. Dynamics of change in the index of the population (Ip) of Maramuresh County (1930-2011)

The situation in Maramuresh area may serve as an example of an integral model of aculturing of national minorities. Their representatives speak fluently both the national Ukrainian and state Romanian languages, preserving their own national identity. Maramuresh Ukrainians, having got the right to study the native language and use it in everyday religious and administrative life, managed to preserve their own national and linguistic identity. Due to mainly Romanian teaching at schools, they managed to integrate completely into the Romanian society, having avoided the conflict between national Ukrainian and Romanian political (civil) identities.

Such state of affairs may serve an example for Romanian community in Ukraine, which is not having the possibility to study the state (Ukrainian) language at the appropriate level, appeared in the state of language segregation.

The censuses indicate one more difference between the two mentioned counties of Romania. In Maramuresh area the number of Ukrainians according to their national self-identification has always exceeded the number of Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainians. In Southern Bukovyna the number of Ukrainian-speaking people exceeds the number of Ukrainians according to their nationality practically during each census.

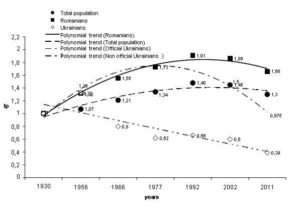

The Romanian population censuses showed that starting from 1956 (even earlier) the most significant demographic losses among Ukrainians of Romania are registered in the Ukrainian community of Southern Bukovyna.

The last Austrian population census of Bukovyna in 1910 registered approximately 34 thousand people in Southern Bukovyna who identified Ukrainian as their native language. It is impossible to estimate the ethnic structure of the population in Southern Bukovyna in 1910 more accurately because a lot of former Ukrainian communities (Seliatyn, Shypit Kameralny and others) are separated nowadays by Ukrainian-Romanian border.

According to the census in Royal Romania in 1930, there lived 14 thousand Ukrainians in Southern Bukovyna (they were identified as Rusyns, Ruthens-Ukrainians, Hutzuls in the census), that constituted 3 per cent of the whole population. There were twice more Ukrainian-speaking people in this part of Romania – more than 24,5 thousand people. At the same time Ukrainians lived densely in 20 communes. According to modern censuses only 18 communes maintain Ukrainian trace, there is not a single Ukrainian in such villages as Briaza and Dzhemenia, and Ipoteshty. There disappeared a numerous community of Ukrainian-speaking Romanians. In the commune Melishivtsi there remained only a few persons of formerly almost 1000 Ukrainian-speaking community.

Table 4. Population of Suceava County

| Years of census | Population

|

||

| Romanians | Ukrainians | Total | |

| 1930 | 354,985 | 14,348 | 472,111 |

| 1956 | 468,508 | 19,142 | 507,674 |

| 1966 | 550,196 | 11,568 | 572,781 |

| 1977 | 614,498 | 8,943 | 633,899 |

| 1992 | 678,510 | 9,530 | 701,830 |

| 2002 | 662,980 | 8,514 | 688,435 |

| 2011 | 590,741 | 5,698 | 614,451 |

Note: data from http://www.insse.ro/cms/files/RPL2002INS/vol4/tabele/t1.pdf

Thus, according to the 2002 census there lived 8514 persons in Suceava County, or 1,2 per cent from the general number of population who identified themselves as Ukrainians. In 2011 the number of such persons decreased almost by 3 thousand – 5698, or 0,9 per cent from the general portion of the population. At the same time in the county there decreased the portion of persons who acknowledge Ukrainian as their native language – from 8497 to 6071 persons in the year 2011.

The previously done analysis indicated the following tendencies: the number of people in Southern Bukovyna who officially acknowledge themselves as Ukrainians decreased by more than two times from 14 thousand to 5,8 thousand people for the last 80 years between the censuses of the years 1930 and 2011 and the number of officially Ukrainian-speaking people decreased by more than four times from 24,5 thousand to 6 thousand people.

Figure 3. Dynamics of change in the index of the population (Ip) of Suceava County (1930-2011)

At the same time there did not happen any mass migration of Ukrainians. It only testifies to mass assimilation which, notwithstanding the change of political regimes in Romanian state, acquired a steady character. The Ukrainian language and identity were not acknowledged at all (in 1930 Ukrainians were registered as Ruthens or Hutzuls) for the period of 80 year. Then for a short after-war period there was a temporary thaw, when the Ukrainian language was introduced in the county schools. Ukrainians of Southern Bukovyna suffered the greatest loss during the governing of Ceaucescu. After 1956 the trend of population index of Ukrainians acquired a clear falling character. Was it the consequence of ousting the Ukrainian language from educational institutions or just a mere assertion of a trend of establishing Romanian identity?

- 3. Peculiarities of Demographic Situation in Southern Bukovyna: Accelerated Assimilation and presence of non-official Ukrainians

In Southern Bukovyna there appeared considerable discrepancies between official and non-official data about the number of Ukrainians – exactly in this part of Romania Ukrainians conceal their identity to a larger extent. A famous expert of International Institute for Humanitarian-Political Research Volodymyr Bruter (2000) calculated the number of Ukrainians in Suceava County in the middle 90s of the previous century in his article “Ukrainians of Southern Bukovyna: problems and guidelines”. He did it on the basis of the data about the usage of native language in everyday life and the results of voting for the lists of Ukrainian national organizations at local and parliamentary elections. The Ukrainian minority makes about 37-45 thousand people in Suceava County according to the researcher. In his opinion, great discrepancy between official and non-official data about the number of Ukrainians in Southern Bukovyna is connected with their double Romanian-Ukrainian identification. V. Bruter thinks that Ukrainians in official communication with the authority, e.g. during the population census, prefer Romanian identification which is most expected (desirable) by the authority.

According to non-official data of the Union of Ukrainians in Romania, there live approximately 50 thousand Ukrainians in Southern Bukovyna.The number is based on the information about the number of population who speak Ukrainian in everyday life in certain settlements. The researcher of Ukrainian population of Southern Bukovyna Andrian Shyychuk at the beginning of 90s made a list of areas of Suceava and Botushany counties where Ukrainians live densely. He divided them into three groups :

1) areas, where Ukrainian population lives compactly, preserving their native language;

2) areas, where Ukrainians are mixed with Romanians but preserved their native language;

3) areas, where Ukrainians are totally assimilated by Romanian population.

However, the data of the census confirmed that even in group I there happened an irreversible loss of Ukrainian identity in a considerable number of villages and communes. The results of the announced censuses of 2002 and 2011 indicate that the number of persons who identify themselves as Ukrainians and Ukrainian-speaking persons inevitably decreases from census to census. The tendencies of assimilating Ukrainians continued and in some places strengthened for the last ten years. According to the census in 2011 Ukrainians constitute the majority only in two communes of the county: Balkivtsi (70per cent) and Izvory Suceavej (54per cent).The number of Ukrainians decreased twice from 1343 persons to 698 in Ulma.

In general, describing the dynamics of the number of Ukrainian population in Suceava County for the last inter-census period from 2002 to 2011, the following tendencies can be mentioned: in communes Balkivtsi, Kyrlibaba and Siret there decreased the number of Ukrainian population which correlated with the general demographic processes in these settlements, which did not influence considerably the portion of Ukrainian population in these settlements. However, in other communes the process of decreasing the number of Ukrainian population was accompanied by a considerable decrease of its portion in the general number of population. These processes were of especially impressive scale in the communes Moldova Sulitsa and Mushenitsa, where the number and the portion of Ukrainians decreased by 2,5 times; in communes Arbore, Kalafindeshty (Serbivtsi) and Vatra Moldovitsey – by three times. Ukrainians suffered the greatest loss in the communes Dermeneshty and Moldovitsa where for the period of ten years their number decreased almost by 5 times.

According to the census of 2011 Southern Bukovyna ‘received’ Turiatka – the village of Chernivtsi oblast where Ukrainian-speaking Romanians live. In Hutzul commune Ulma, where the number of Ukrainians decreased from 2001 by 645 persons and constitutes 698 persons, live simultaneously 1156 persons who acknowledged Ukrainian as their native language. This is another example of double (Ukrainian-Romanian), or even triple Ukrainian-Romanian-Hutzul identification of a significant group of population.

The only exception of the general tendency became the results of the census in 2011 in Hutzul commune Izvory Suceavej, where the portion of Ukrainian and Ukrainian-speaking population increased by 2per cent.

In general inconsolable processes for Ukrainian population of Southern Bukovyna became another confirmation of the conclusions of OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities who in 2006 in his official letter to addresses of foreign affairs ministers of Ukraine and Romania, namely in the recommendation section mentioned verbatim the following:

”The situation of the Ukrainian minority in the Romanian region of Suceava is characterized by strong assimilative tendencies. A considerable number of persons with an ethnic Ukrainian background declared themselves Romanian rather than Ukrainian in the 2002 census, although in private many of them preserve some, albeit weakly developed, Ukrainian cultural identity. The majority of Ukrainians cannot read and write Ukrainian and prefer their children receive an entirely Romanian language education. While voluntary assimilation would be a fair characterization of the situation today, its root causes go back to the repressive policies of the pre-1989 Romanian Communist regime. In this view, the Romanian authorities have a particular responsibility to provide necessary opportunities and encourage those Ukrainians who wish to preserve, develop and strengthen their ethno-cultural identity in parallel to their civic identity of Romanian citizens” [6].

The last census indicated one more tendency: in Suceava County there appeared a Ruthen community represented by 128 persons in the commune Dermaneshty. Taking into consideration that in 2001 in this commune there did not live any Ruthen, the number of Ukrainians constituted 298 people, we have grounds to assert that part of Ukrainians changed their modern Ukrainian identity to pre-modern Ruthen one. There happened the so called inverse ethnic evolution. Its consequence was not only five-time decrease of the number of Ukrainians in this community but also decrease of the total number of East-Slavic population of the commune Dermaneshty by 1,5 times for the period of ten years.

- 4. The Basic Factors of Ethnic Development of Ukrainians in Romania

“Priests and teachers played the main role both for Romanians and Ukrainians”, asserted the famous German researcher Mariana Hausleitner (2001) in her analysis of national projects in Bukovyna at the beginning of the XXth century. On the turning point of the XXth – XXIst centuries ethno-cultural, ethno-religious and ethno-political processes last with a more or less intensity, mutually influencing each other and acquiring new and sometimes unexpected forms.

- 5. Education

One of the most important elements of forming ethnic identity is ensuring educational rights for national minorities. After World War II in the villages and towns of densely inhabited residence of Ukrainians in Romania all school subjects were taught in Ukrainian. School was the centre of Ukrainian life: religious and national holidays, memorable days of great Ukrainians etc, were celebrated here. Positive influence of school on preserving Ukrainian identity is vividly represented in the data of 1956 census form. That year an increase in the number of Ukrainian population was registered by one-third in comparison with the census of 1948 in all counties of Romania. This increase took place in Southern Bukovyna and Maramuresh area.

Starting from 1964 all cultural-educational work of Ukrainians in Romania suffers from pursuit. Almost all schools with the Ukrainian language teaching were eliminated (there worked only a Ukrainian department in the secondary school in Siget). Ukrainian local family names were abolished to be used in publications.

In modern Romania there are no preschool institutions and primary, eight-year, secondary schools where teaching is done in Ukrainian. The Ukrainian language is taught as a subject (mostly optionally and at the written request of parents) in 63 schools in the areas of compact residence of Ukrainian minorities. Approximately seven thousand pupils study Ukrainian there. Inspectorates on the Ukrainian language training are formed in the counties: Maramuresh, Suceava, Botoshany, Satu Mare, Arad, Tymish, Tulcha, Karash Severyn. Ukrainian is studied in the following settlements:

– County Maramuresh: Siget Marmaritsey, Rivna Vyshnia, Rus Poliana, Ruskova, Krychunov, Remeti;

– County Satu-Mare: Mikula

– County Karash Severyn: Kornutsel-Banat, Kopchele, Zoria;

– County Arad: Tyrnova;

– County Tymish: Poganeshty, Bethausen, Lugozh, Shchuka;

– County Tulcha: Kalyna (commune Myrygliol);

– County Suceava: the town of Siret, Balkivtsi and Nehostyna (commune Balkivtsi), Shcherbivtsi, Melishivtsi, Brodina (commune Izvorele Suceavej), Ulma.

– County Botoshany: Rogozhesty (commune Kindeshty) and others.

Teaching in Ukrainian is conducted only in T. Shevchenko highschool (the town of Siget, Marmatsiey, Maramuresh area). The educational institution was revived in 1997. 660 pupils in 13 forms from pre-school to secondary education study in Ukrainian.

It is planned to renew a Ukrainian highschool by 2013 on the basis of Latsku Vode highschool (the town of Siret, Suceava County). At present, there are three Ukrainian forms at Latsku Vode highschool.

What concerns higher education there are departments of the Ukrainian language opened 50 years ago in three Romanian universities, including Bucharest University.10-15 students annually study at the departments.

- 6. Religion

The majority of the Ukrainian population in Romania was orthodox; Greek-Catholics prevailed mostly in Maramuresh area and in Banat. After the elimination of Greek-Catholic Church in Romania in 1948 the believers went over to orthodoxy. Orthodox Ukrainian Vicariate was revived in Romania in 1996, whose residence is located in the town of Siget-Marmaritsey. It constitutes 25 parishes uniting 52 thousand believers according to the church data. Orthodox Ukrainian Vicariate is under jurisdiction of Patriarchate of Romanian Orthodox Church. Divine services and sermons of Romanian Orthodox Church almost everywhere are given in Romanian. That is the reason why church remains one of the active means of Romanization.

There was renewed General Vicariate of Ukrainian Greek-Catholic church with a centre in the town of Radivtsi of Suceava County in 1996 in Romania. The church consists of Bukovynian (5 parishes), Maramuresh (5 parishes) Satu-Mare (7 parishes) deaneries, and also Banat County (2 parishes) and numbers approximately 6 thousand parishioners. The Sermons are mainly delivered in Ukrainian in Greek-Catholic church.

- National organizations and Elections

A famous researcher of national movements in Eastern Europe, American sociologist Rogers Brubaker, having analyzed experience of institutionalizing Hungarian minority in Romania, mentioned that there exists a great “gap between national organizations (Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania – author’s comment)” and the community (of Hungarians), which they allegedly represent»[2004: 24]. The gap between national organizations of Ukrainians in Romania and Ukrainian community is much deeper. The reasons for that situation will be explained further.

Three national-cultural organizations of Ukrainians were officially acting in Romania at one or other time: Union of Ukrainians in Romania (further – UUR), Democratic Alliance of Ukrainians in Romania and National Front of Ukrainians in Romania. It should be mentioned that the authority of Romania officially cooperate only with Union of Ukrainians in Romania (the first registered public organization), which has its centres in the place of compact residence of Ukrainians. It also has its representative in the Parliament of Romania and the main thing – it has a considerable state financing for statute activity. The other two public organizations of Ukrainians after unsuccessful attempts to receive the above mentioned preferences of the Romanian government haven’t been working actively in the recent time.

In Romania, unlike Ukraine, legislative preconditions for representation of national minorities are created in the Parliament. Such a norm has been in force since 1992 and has received approval in the new Law about elections to the chamber of deputies and Senate of Romania. The Law presupposes the right of ethnic communities that are represented in the Council of national minorities for representation in the lower chamber of the Parliament of Romania. According to the Law the representatives of national minorities are given 18 mandates out of 314. National-cultural societies of ethnic minorities are equated to the status of political parties by election legislation of Romania. To participate in elections, organizations of national minorities who are members of the Council of national minorities should submit a list of organization members to the Central Election Bureau. It must include not less than 15 per cent of the whole number of citizens, who, according to the last census, identified themselves with a certain national minority.

The list of the Union of Ukrainians in Romania (UUR) received support of 9338 electors at parliamentary elections 2012. Ukrainians are the fourth community of Romania according to the number of the population. However, the national list of UUR received 7353 votes, and this makes 2 thousand less than in 2008. The result is the twelfth one among national-cultural organizations. Such electoral “success” indicates low support of candidates from UUR among Ukrainian community. Having analyzed regional support of the UUR list, we encounter some more peculiarities. 482 electors from Maramuresh County (taking into consideration the fact that 30 thousand ethnic Ukrainians live here) and 599 voters from Suceava County (more than 6 thousand Ukrainians) voted for the UUR list. Simultaneously, UUR was actively supported by the residents of counties where there are few Ukrainians according to the census data. There were 476 votes for the UUR list (53 Ukrainians according to the census), 120 votes – in the County of Hargita (17 Ukrainians according to the census).

The election system, introduced in Romania, allowed both Ukrainians (50 thousand people) and Ruthens (100 times less) to have one mandate in the Parliament. It should be mentioned that the list of Ruthens receives more support from year to year. Thus, in 2012 it received 5203 votes, that makes almost 700 votes more than in 2008 and tens of times more than the number of Ruthens themselves. There lived 298 Ruthens in Romania according to the 2002 census.

Such electoral discrepancies to the census data make us think about the efficiency of election legislation of Romania, the section of giving preferences for representatives of national minorities.

- Participation in the authorities

The Lund recommendations from the OSCE on the Effective Participation of National Minorities in public life and Ljubljana Guidelines on Integration of Diverse Societies recommend engaging representatives of national minorities in the work of public authorities. However, representatives of Ukrainian community have never been appointed to the leading posts in the authorities. Maximum that they managed to achieve was the level of advisers and ordinary workers. Especially blatant is the situation in Southern Bukovyna. Ukrainians not only weren’t engaged in the work in authorities, even in education departments Romanians were appointed to the positions of Ukrainian language inspectors and not Ukrainians (it’s mentioned in the monitoring report). The authority in Suceava district created such conditions that in Ukrainian villages Romanians were appointed to the positions of Primars, namely in the villages of Negostyna and Balkivtsi (where Ukrainians constitute more than 70% of the population, a Romanian, who does not know Ukrainian, was appointed Primar) .

- Relation with kin-state

During the times of Ukraine being a member-state of USSR, different attention to Ukrainian Diaspora in Romania was paid in different times. In the after-war time systematic help to Ukrainians in Romania on the part of Ukraine was felt. There were given books, methodological manuals, fiction. During the first years of introducing Ukrainian schools in Romania, at the beginning of the school year the majority of pupils of the respective schools received high-quality books (both in content and typography) for free and this contributed to formation of positive image of Ukraine as a historic Motherland of all Ukrainians. However, later on, Ukrainian SSR reduced help for Ukrainians in Romania and in times of Ceausescu this help stopped coming.

During the times of independence, the authorities of Ukraine were trying to raise the question of ensuring humanitarian rights of Ukrainians, namely right for education in their native language, on interstate negotiations. In order to solve the questions there was formed an intergovernmental committee on the issues of Ukrainians in Romania and Romanians in Ukraine. Since 2007 the Committee hasn’t held a single meeting and implementation of the previous decisions was systematically ignored by the Romanian party. However the level of this interest is much lower than the level of care about the Romanian community in Ukraine on the part of Romania.

Ukraine, according to both national (Yaroslav Hrytsak, Volodymyr Yevtukh) and foreign (namely, the above mentioned Rogers Brubaker), counted on formation of a political nation (A. Smith civil-territorial model) on the basis of all nationalities living on its territory. According to this model Ukrainian Diasporas were given a secondary role in building of a state, they were not considered as an important element in its formation. In particular, in Ukraine there has not been formed a governmental body which would care about Ukrainians living abroad (in Romania there is a Department of Romania from everywhere), Ukrainians from Diaspora did not receive any important political posts of the authority of Ukraine etc. Besides that a complicated social-economic situation in Ukraine did not contribute to providing money for saving identity of Ukrainians in other countries.

Border regions of Ukraine, namely Zakarpatska and Chernivtsi oblasts, attempted to take upon themselves a certain role in the interrelation with Ukrainian community of Marmorosh area and Southern Bukovyna. However, the resource of regional authorities used to be and is rather limited. Besides that, regional authorities can not solve questions with central governmental bodies.

Conclusion

Summing up, we can draw the following conclusions:

– modern Romanian legislation guarantees ethnic communities living on the territory of the country rights for national, cultural and political development. But Romanian Parliament has still not adopted the draft Law on the Status of National Minorities which has been under consideration in various forms. Lack of the basic law causes inconsistence of some legal acts of Romania what concerns national minorities’ rights and this is mentioned in the report of Advisory Committee of the Council of Europe on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities ;

– the census data indicated a correlation between the number of the population of the Ukrainian Community in Romania and the policy of the country that concerns ensuring the rights of national minorities. The situation in Southern Bukovyna is especially vivid. The policy of Romanization caused the decrease in the number of Ukrainians by four times during the last 80 years;

– there are at least three factors which influence preservation of national minorities’ identity: education (school), religion (church), authority of local leaders;

– most researchers consider the influence of education in the native language and usage of the language in the religious sphere to be decisive for preserving national identity. Asserting this position we single out one more factor – leaders of the community. Ukrainians did not have the possibility to get education in their native language during the period of 50 years in Maramuresh area as well as in Southern Bukovyna. The Ukrainian language has not been used in the religious sphere either. However, the Ukrainians of Maramuresh area did not lose their own identity and did not assimilate unlike the Ukrainians from Southern Bukovyna. The peculiarity of the County of Maramuresh is availability of local leaders of the Ukrainian community who supported Ukrainian identity despite general national tendencies of assimilation;

The census data testified to the fact that an assimilation model of “acculturing the Ukrainian community” is being realized in Southern Bukovyna.

There are several reasons for that:

Firstly, the process of institutionalization of Ukrainian community in Romania is carried out with considerable difficulties. The community does not trust national-cultural societies, representing it (the results of voting for lists of UUR testify to that fact), and educational institutions which could become the basis for grouping of Ukrainians via educational policy of Romanian governmental structures, have not been formed. Orthodox religious communities of Ukrainians in Romania, because of the policy of ecclesiastic leaders of Romanian churches, directed at Romanization of national minorities, have not become centres for revival of Ukrainian identity.

Secondly, Ukrainians in Southern Bukovyna were drawn aside from work in the authorities and were not able to form a police directed at the development of the community.

Thirdly, Ukraine because of various reasons, the main one being the fact that Ukrainian Diaspora was not considered as an element of building Ukrainian nation and Ukrainian statehood, could not compensate to Ukrainian community insufficient attention on the part of Romanian authority.

A civil-territorial model of building a Ukrainian nation (as a consequence – insufficient attention to Ukrainian community in Romania) and ethnic-genealogical model of building a Romanian nation (excessive attention to Romanian community in Ukraine) led to assimilation processes among Ukrainian community predominating in Romania, and segregation processes among Romanian community predominating in Ukraine. It was noted when holding a common monitoring of adherence to the rights of national minorities of Ukraine and Romania in 2007.

[1]Constituţia României. [Constitution of Romania]. http://www.cdep.ro/pls/dic/site.page?id=339

[2]Conventia Cadru pentru Protectia Minoritatilor Nationale. [Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities] http://www.anr.gov.ro/docs/legislatie/internationala/Conventia_Cadru_pentru_Protectia _Minoritatilor_Nationale.pdf

[3]Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Third Opinion on Romania adopted on 21 March 2012. http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/minorities/4_Events/News_Romania_Com_09apr2013_en.asp

[4]Legea de ratificare Carta Europeana a Limbilor. [European Charter of regional and minority languages] http://www.dri.gov.ro/documents/B1-Legea%20de%20ratificare%20Carta%20 Europeana%20a%20Limbilor.pdf

[5]Legea Educatiei Nationale. [Law on the national education]. http://www.edu.ro/index.php/legaldocs/14847

[6]The Note on the Joint Monitoring Missions in Ukraine and Romania by High Commissioner on National Minorities OSCE- 16 November 2006

References

Berry, J.W. ‘Conceptual approaches to acculturation// Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement and applied research’. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, (2003). – pp. 17–37.

Brubaker, Rogers. Ethnicity without Groups. USA: Harvard College, 2004

Constituţia României. Accessed 5 December.[Constitution of Romania]. http://www.cdep.ro/pls/dic/site.page?id=339.

Conventia Cadru pentru Protectia Minoritatilor Nationale.[ Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities] http://www.anr.gov.ro/docs/legislatie/ internationala/ Conventia_Cadru_pentru _Protectia _Minoritatilor_Nationale.pdf. Retrieved: August 04, 2014.

Die Ergebnisse der Volks- und Viehzählung vom 31. Dezember 1910 im Herzogtume Bukowina nach den Angaben der K. k. statistischen Zentral-Kommission in Wien. Chernivtsi, 1913. –

Dimensiuni ale învăţământului minorităţilor naţionale din Români. EDIŢIE JUBILIARĂ 1993-2003. – Bucharest, 2003. – P. 38

Hausleitner M. Die Rumänisierung der Bukowina: Die Durchsetzung des nationalstaatlichen Anspruchs Grossrumäniens 1918-1944. [The Romanization of Bukovina: The enforcement of the nation-state claim of Greater Romania 1918-1944]– München: Oldenbourg, 2001.

Legea de ratificare Carta Europeana a Limbilor. Accessed 8 December.http://www.dri.gov.ro/documents/B1-Legea%20de%20ratificare%20Carta%20 Europeana%20a%20Limbilor.pdf

Legea Educatiei Nationale.[Law on National Education]. Accessed 10 December. http://www.edu.ro/index.php/legaldocs/ 14847

Legea nr. 373/2004 pentru alegerea Camerei Deputatilor si a Senatului Accessed 10 December. [ Law on the elections for the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate] http://legislatie.resurse-pentru-democratie.org/373_2004.php

Recensământul general al populaţiei României dîn 29 decemvrie 1930. [General census of the population of Romania of 29 Decemvrie 1930]. Bucharest, 1938.

The Note on the Joint Monitoring Missions in Ukraine and Romania by High Commissioner on National Minorities OSCE- 16 November 2006.

Summary of the 9 December 2012 Chamber of Deputies of Romania election results. Accessed 5 December. http://www.becparlamentare2012.ro/statistici%20rezultate%20finale.html

Smith, Anthony D. National identity, Penguin Books, 1991

Populatia dupa etnie la Recensamintele din perioada 1930-2002, pe Judete. [Population by ethnicity in censuses in the period 1930-2002]. Accessed 2 December. http://www.insse.ro/cms/files/RPL2002INS/vol4/tabele/t1.pdf

Брутер, Владимир. ‘Украинцы Южной Буковины: проблемы и ориентиры’ [Ukrainians in Southern Bukovyna: issues and guidelines]. Cборник научных конференций «Трансграничное сотрудничество Украины, Молдовы и Румынии», 2000.

Договір про відносини добросусідства і співробітництва між Україною та Румунією від 2 червня 1997 року [Agreement between Ukraine and Romania about relations of good-neighbourly relations and cooperation from June 2, 1997] // Захист прав національних меншин в Україні: збірник нормативно–правових актів. – К.: Держкомнацміграції, 2003 – С.260

Рендюк, Теофіл. Українці Румунії: національно-культурне життя та взаємовідносини з владою[Ukrainians in Romania: national culture evolution and the relationship with the government], Київ: Інститут історії України НАН України, 2010.

Шийчук, Адріан. ‘Українці Південної Буковини: «quo vadis?»’ [Ukrainians in Southern Bukovyna: «quo vadis?»]. http://buktolerance.com.ua/?p=2471.Accessed 5 December 2013.

Scridb filter

Leave a Reply